Child Labor and India's Football-making Industry

India is the world's second (following Pakistan) largest producer of footballs and other inflatable balls. Between April 1999 and February 2000, India's production reached almost US$ 18 million (Rs. 7,854. 76 lakhs). United Kingdom imported a total of US$ 6. 86 million for the same period. Other important European importing countries are France, Germany, Spain, Italy and The Netherlands. Besides inflatable balls, badminton rackets, shuttle cocks, cricket balls and bats, hockey sticks and different kinds of gloves and protective equipment are also manufactured. There are 364 sports goods exporters registered with the Sports Goods Export Promotion Council (SGEPC) in India.

According to the Sports Goods Manufacturers and Exporter's Association in India, the total number of persons working in the industry is about 30,000. A report by Christian Aid however gives a figure of around 300,000 people working in the industry, "either in the 1,500 factories and smaller manufacturing units or as subcontracted home-workers"

It is not fully clear how this large difference can be explained, but it can be assumed that the former figure does not include the home-based workers who are working for the manufacturers/exporters via the contractors. The number of home-based workers can only be roughly estimated as there are no reliable data on them yet. If the figure of 300,000 is correct this would mean that nine out of ten workers in the sports goods industry are in the informal, unorganized sector.

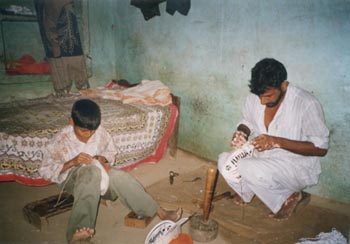

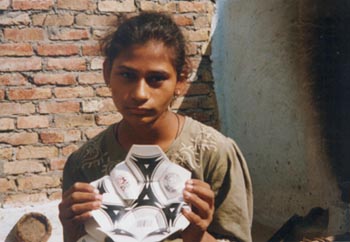

The V. V. Giri National Labour Institute of India (NLI), as commissioned in 1997 by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, studied the child labor situation in the Indian sports industry. Its report gives a detailed account of the child labor issue. Being the most comprehensive survey on the issue thus far, although only limited to the Jalandhar area, the report estimates that about ten thousand children are working in sports goods production. Of these about 1,350 are only working (and not going to school) while the rest are both working and school going. While 92% of the working children are stitching footballs, 8% of the child laborers in Jalandhar and its surrounding villages make other sports goods such as shin pads, cricket balls, rackets and shuttles.

The report makes a distinction between children who are only working (OW) and not going to school, children who are working and school going (WSG), children who are only school going (OSG) - although they might be doing households chores - and not working and not school going children (NWNSG).

The survey found that three out of four families reported children who are either only working or combining education with work.

Footballs are stitched by children from five years and older. However, 'only' 11% of the OW children are between five and nine, while 26% are between ten and twelve. The rest (63%) are thirteen or fourteen years old. Two-thirds of the WSG children are between five and twelve, indicating that most children start to stitch footballs when they are quite young. The work participation of boys and girls in stitching balls is almost the same.

The work intensity of the stitching children is high. A six-year-old 'only working child' spends on average seven and a half-hours stitching balls, while a thirteen-year-old child spends nine hours of work. Children who go to school and work have to shoulder a bigger work burden: nine hours when they are six and almost eleven hours when they are thirteen. It is also striking that a quarter of the OW children work at night, while 14% of the WSG children do so.

Most children leave school from ten years of age onwards. There is a relatively high rate of school attendance of children between five and nine years old. However, with the average number of working hours (besides school work) being more than three hours each day after the age of ten, the pressure builds up to leave school: "The work pressure finally leads to dropping out of school. The data suggests that 90% of drop-outs have turned into full-time workers. The NLI report states that more than half of the respondents say that financial problems or the need to assist in family work forced the children to leave school and start working full-time. More than a quarter of the respondents reported lack of interest in school as the main reason for dropping out. The NLI report sums up the impact of child work on education as follows: "Child work renders school education futile in the perception of both parents and children. Parents do not insist and children lose interest.

There are many factors to consider in this issue. The quality of schooling combined with the lack of school-going tradition (especially for girls), the pressure of work once started and the fact that most stitchers are socially discriminated 'Dalits' might ultimately be more important than the often, and perhaps more easily voiced, financial reasons to drop out.

According to representatives of the sports goods industry, the problem of child labor has been substantially reduced since the research was done by the NLI. In 1998, sports goods exporters formed the Sport Goods Foundation of India (SGFI). It now has thirty-two members. The members contribute 0. 25% of their earnings from manufacturing footballs to support an inspection and child labor rehabilitation program. Mr. S. Wasan, the SGFI secretary, said that the foundation expected an external monitoring group (Societe Generale de Surveillance or SGS) to find only a few working children, because of the increased awareness on the issue. This expectation is not surprising because SGS found only one child after the first round of monitoring almost 200 stitching locations and 70 children after covering almost 75% of the stitching locations in June 2001. Another SGFI official felt that the problem is now much less compared to two years ago. He particularly expected the number of 'only working children' to be very small now.

Legal Work

Almost five years ago FIFA agreed on a 'Code of Labour Practice' with the International Federation of Trade Unions (ICFTU) for FIFA licensed products, particularly footballs. The code however was never signed or implemented. Instead, programs in Pakistan and recently in India were started to eradicate child labor from the industry. In addition, the contracts signed by the football importing companies with FIFA contain clauses on labor conditions that are based on the Code of Conduct of the World Federation of Sporting Goods Industry. These clauses are less stringent than those in 'the original FIFA Code'. For example, provision on 'fair wages' is missing. Even these contracts however are violated in India on several points.

Concluding Statement

Bringing an end to the use of child labor and guaranteeing basic labor rights in the sports goods industry of course go beyond the influence of FIFA and other football associations. Therefore all companies, regardless of their relation to FIFA, should have a code of labor practice which is at least as good as the original FIFA Code and is independently monitored and verified.

No comments:

Post a Comment